A World Apart: The Distinctive Character of Japanese Green Tea

If you have ever sipped a Chinese green tea like Longjing and then tried a Japanese Sencha, you might have wondered: How can two teas made from the same plant taste so completely different? The answer lies not in the leaf itself, but in the hands of the artisan and the ancient techniques they employ. Japanese green tea represents a parallel evolution of tea culture—one that emphasizes freshness, umami, and a delicate vegetal elegance that stands in beautiful contrast to the nutty, toasted character of Chinese greens.

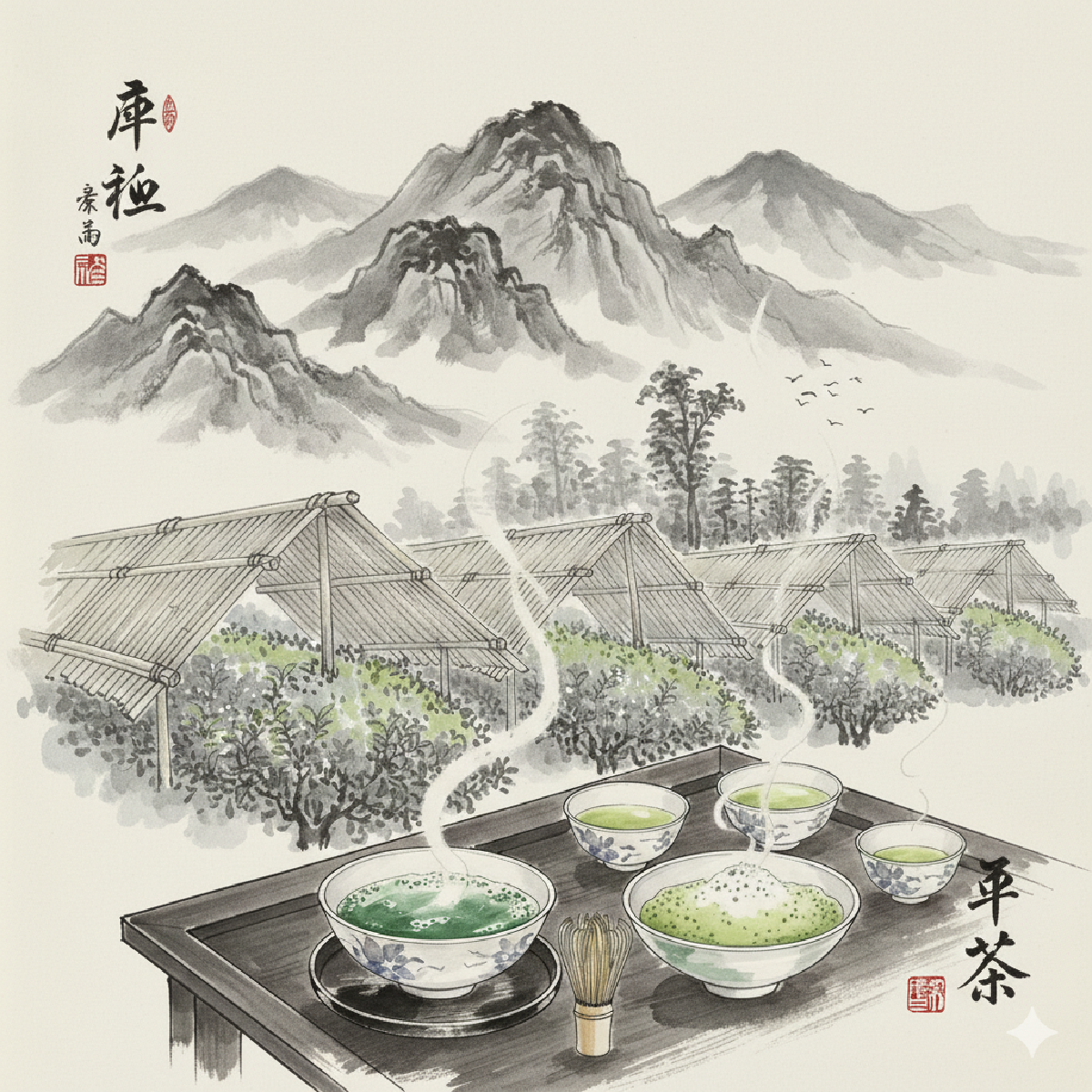

While Chinese green teas are pan-fired in large woks to stop oxidation, Japanese green teas are steamed—a method that preserves the leaf’s vibrant green color and fresh, grassy character. This fundamental difference creates a tea experience that is uniquely Japanese: bright, savory, and often described as having a “marine” or “seaweed-like” quality that tea lovers either adore or find challenging. Whether you are new to Japanese tea or looking to deepen your understanding, this guide will help you navigate the world of steamed elegance.

The Steaming Method: Why Japanese Tea is Steamed Instead of Pan-Fired

The defining characteristic of Japanese green tea production is the steaming process (called mushi in Japanese). Unlike Chinese green teas, which are pan-fired in hot woks to “kill the green” and stop oxidation, Japanese teas are exposed to steam for 30-60 seconds immediately after harvesting. This rapid heat treatment denatures the enzymes that would cause oxidation, but it does so without the toasting effect of direct contact with a hot surface.

The steaming method was developed in Japan during the 18th century, likely as an adaptation to the country’s humid climate and the need for a more efficient processing method. The result is a tea that retains more of its natural chlorophyll, giving it that characteristic deep green color and preserving the fresh, vegetal flavors that would be lost in pan-firing.

When you compare the two methods:

- Pan-firing (Chinese): Creates nutty, toasted, sometimes smoky notes. The leaves are often flat or curled.

- Steaming (Japanese): Preserves fresh, grassy, vegetal notes with a pronounced umami quality. The leaves are typically needle-like or fine-powdered.

This isn’t just a matter of preference—it’s a fundamental difference in philosophy. Chinese green tea celebrates the transformation of the leaf through fire, while Japanese green tea celebrates the preservation of the leaf’s natural character through steam.

Major Varieties Overview: From Everyday to Ceremonial

Japanese green tea comes in many forms, each suited to different occasions and preferences. Understanding these varieties is your first step into Japanese tea culture.

Sencha (煎茶)

The most common Japanese green tea, accounting for about 80% of production. Sencha is made from the first flush of leaves, steamed, rolled, and dried. It has a balanced flavor profile—grassy, slightly astringent, with a refreshing finish. This is the “everyday” tea of Japan, perfect for morning or afternoon drinking.

Gyokuro (玉露)

The premium shaded tea. About three weeks before harvest, the tea bushes are covered with shade cloths, reducing sunlight by up to 90%. This stress causes the plant to produce more amino acids (especially L-theanine) and less catechins (which cause bitterness). The result is a tea with intense umami, a deep green liquor, and a price tag to match. Gyokuro is typically brewed at lower temperatures (50-60°C) to extract its delicate sweetness.

Matcha (抹茶)

The powdered tea used in the Japanese tea ceremony. Like Gyokuro, Matcha is made from shade-grown leaves, but instead of being rolled and dried, the leaves are ground into a fine powder. When you drink Matcha, you’re consuming the entire leaf, which means you get all the nutrients and caffeine. It has a rich, creamy texture and a slightly bitter, vegetal taste that pairs beautifully with sweets.

Bancha (番茶), Hojicha (焙じ茶), and Genmaicha (玄米茶)

Bancha is a lower-grade tea made from larger, more mature leaves—milder and lower in caffeine. Hojicha is roasted green tea that breaks the “green” stereotype with its nutty, toasty flavor and very low caffeine. Genmaicha blends Sencha with roasted brown rice, creating an affordable, approachable tea perfect for beginners.

The Umami Factor: What Creates That Savory, Marine Quality

One of the most distinctive characteristics of Japanese green tea is its umami taste—that savory, brothy quality that makes your mouth water. This is not a flavor you typically find in Chinese green teas, and it comes from a combination of factors unique to Japanese production methods.

The primary contributor to umami in Japanese tea is L-theanine, an amino acid that naturally occurs in tea leaves. When tea plants are shaded (as with Gyokuro and Matcha), they produce more L-theanine and less catechins (the compounds responsible for bitterness). The steaming process also helps preserve these amino acids, whereas pan-firing can break some of them down.

Additionally, Japanese green teas often contain higher levels of glutamic acid and other amino acids that contribute to that savory, almost “seaweed-like” quality. This is why high-quality Sencha or Gyokuro can taste almost like a light vegetable broth—it’s not your imagination, it’s chemistry.

The umami profile is most pronounced in Gyokuro (intense, almost overwhelming), high-grade Sencha (balanced umami with vegetal notes), and Matcha (rich, creamy umami when properly prepared). This is why Japanese green tea pairs so well with food—the umami complements savory dishes in a way that other teas cannot.

Key Production Regions: Terroir Across the Islands

While Japan is a relatively small tea-producing country compared to China, its tea regions each have distinct characteristics shaped by climate, altitude, and tradition.

Shizuoka (静岡) is Japan’s largest tea-producing region, accounting for about 40% of total production. Located on the Pacific coast with a mild climate and abundant sunshine, Shizuoka produces primarily Sencha known for bright, refreshing character and good balance of umami and astringency.

Uji (宇治), located near Kyoto, is the historic heart of Japanese tea culture, producing tea for over 800 years. Famous for premium Gyokuro and Matcha, Uji’s misty climate and traditional farming methods create teas with exceptional depth and complexity. When you see “Uji” on a tea label, you’re getting something special.

Kagoshima (鹿児島), the southernmost tea region, is known for modern, efficient production methods. The warmer climate allows for multiple harvests per year, and the region is known for innovation in organic and sustainable farming.

Basic Brewing Guidelines: Water Temperature and Steeping Times

Japanese green tea requires a gentler touch than Chinese greens. The key is lower temperature and shorter time to extract the delicate umami without releasing too much bitterness.

| Tea Type | Water Temperature | Steeping Time (First Infusion) |

|---|---|---|

| Gyokuro | 50-60°C (120-140°F) | 2-3 minutes |

| High-grade Sencha | 60-70°C (140-158°F) | 30-60 seconds |

| Standard Sencha | 70-80°C (158-176°F) | 30-60 seconds |

| Bancha/Hojicha | 80-90°C (176-194°F) | 30-60 seconds |

| Matcha | 70-80°C (158-176°F) | Whisked, not steeped |

Pro Tip: If you don’t have a thermometer, boil water and let it cool for 2-3 minutes before pouring over Sencha. For Gyokuro, let it cool for 4-5 minutes, or pour boiling water into a cool vessel first to bring the temperature down quickly.

Japanese green tea can typically be steeped 2-3 times, with each infusion revealing different aspects. The first infusion is often the most umami-forward, while later infusions may be more astringent or vegetal. For second and third infusions, use shorter steeping times (10-20 seconds) since the leaves are already open.

How to Identify Quality Japanese Green Tea

You don’t need to be a tea master to spot quality Japanese green tea. Use your senses and look for these indicators:

| Feature | High-Quality (Premium) | Lower-Quality (Standard) |

|---|---|---|

| Leaf Appearance | Fine, needle-like, uniform dark green; no stems or broken pieces | Coarse, uneven, may include stems or yellow leaves |

| Dry Aroma | Fresh, vegetal, slightly sweet; no stale or fishy smell | Weak aroma, or stale/oxidized smell |

| Liquor Color | Bright, clear yellow-green (Sencha) or deep emerald (Gyokuro) | Dull, brownish-green, or cloudy |

| Taste | Smooth umami, balanced sweetness and astringency, no harsh bitterness | Bitter, astringent, or flat; lacks umami |

| Aftertaste | Lingering sweetness (amami) and clean finish | Harsh or metallic aftertaste |

Understanding Japanese Tea Grades

Japanese tea grading can be confusing, but here are the basics:

- Shincha (新茶): “New tea” from the first harvest of the year, highly prized

- Ichibancha (一番茶): First flush, highest quality

- Nibancha (二番茶): Second flush, lower quality

- Sanbancha (三番茶): Third flush, lowest quality

Look for harvest dates on packaging—fresher is better. Japanese green tea loses its vibrant character within 6-12 months, so check for production dates and buy from vendors who store tea properly (cool, dark, airtight).

Japanese green tea offers a completely different experience from Chinese greens—one that celebrates freshness, umami, and the subtle art of steaming. Whether you start with an approachable Sencha or dive straight into the deep umami of Gyokuro, you’re entering a world of flavor that has been refined over centuries. For your first exploration, I recommend a high-grade Sencha from Shizuoka—it offers the perfect introduction to that distinctive Japanese character without the intensity (or price) of Gyokuro.